Last week, I swirled around the square format and its aesthetic arc across decades. I find it knocked off a perch in a continued exploration across culture and society.

Beyond The Fame: The Square, Part 2.

Friday Find: Burn It All.

Don’t Believe: Be Sceptical.

With: You must hear about Lesotho; Kpop training; non consensual AI.

1. The Square, Part 2: Beyond the Frame

Last week, I looked at the square format in photography, and across media. We saw how it entered our world courtesy of technological demands, gained cultural weight through aesthetics and social context, then faded away; only to be given primacy once more, again by technology. What drew me further into this exploration was not just the aesthetic arc, but also how we could see— across the decades— that creativity is both shaped and liberated by what can’t be done. A geometrical shape has been both a constraint and a catalyst.

In fact, it is goes beyond that, often serving as a blank canvas for cultural interpretation, perspectives and adaptation. What’s that, you say- so much pontification about the shape of a photograph? Maybe, once you think of it, you will notice how its presence (and absence) influence the media we consume. Come then, let’s explore how much cultural travel this shape has actually managed.

(Read Part 1 here).

When we left off, Instagram had mandated the square in its app, its geometry spilling across other platform and media, turning a once-elite, once-arty photographic format into our visual vernacular. But as with much in technology and culture, the pendulum was to swing again.

You're so square, baby, I don't care. _Elvis Presley

The Vertical Revolution

In 2015, Instagram gave in to the brief but relentless assault of the vertical. The little pocket computers we have chosen to call phones were influencing much of our information age, a very visual age. Vertical video began its ascendance through the likes of Snapchat and TikTok. Amidst resistance from ‘old school’ creatives and consumers comfortable in their symmetrical windows to the world, the tall, narrow format started to feel natural. After all, it is how we hold our phones. As video gained ruthless primacy, our vertical visual experience became immersive and full-screen; the square couldn't match it.

After five years of ‘square tyranny’, as some referred to it (”Rejoice: The iron-fisted reign of the square is dead”, proclaimed Wired), Instagram made a pivotal change by allowing non-square photos on its platform- the square was now merely ‘optional’.

"Square format has been and always will be part of who we are. That said, the visual story you're trying to tell should determine the format.” _Instagram

Instagram would then go on to introduce "Stories" and "Reels"—both vertical formats cannibalised from its competitors. As we well know, this vertical revolution swept through social media. But our friendly, elegant square didn't disappear— it simply found its place in a more complex visual ecosystem. The vertical format may have become ubiquitous, but it is an upstart when compared to the cultural resonance the square has accumulated.

Across Cultures

The square's presence across photography illuminates cultural identities, social statements and political realities across continents. Some postcards from this global journey?

Technological Travel

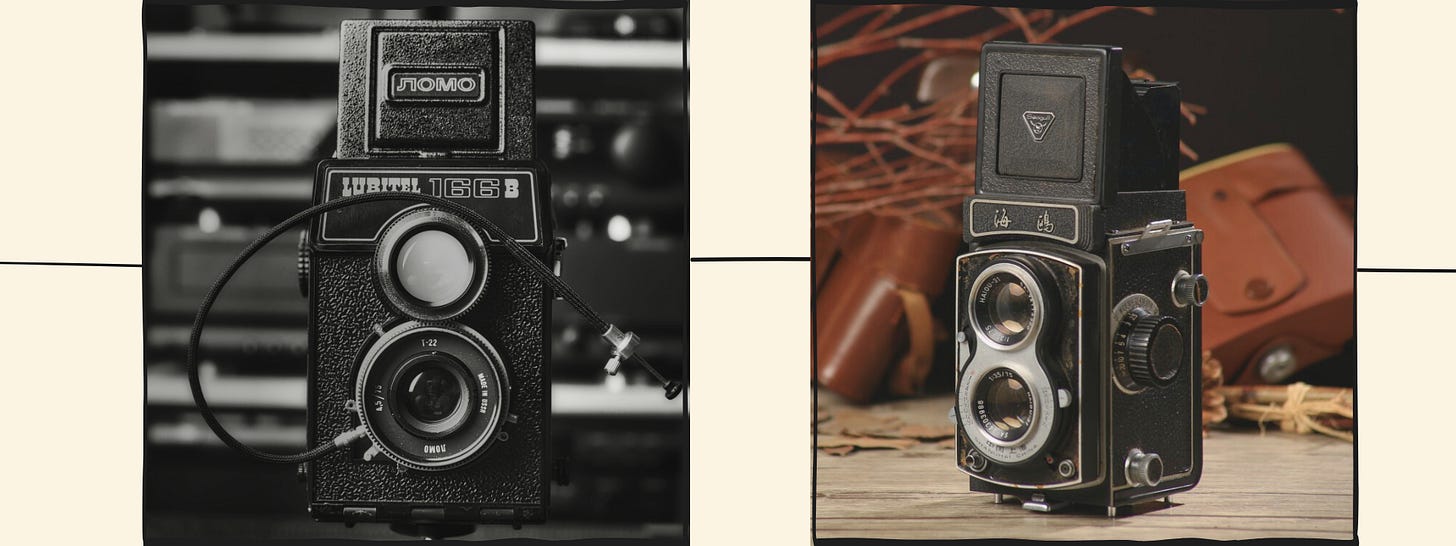

The Cold War era witnessed a parallel development of square format technologies outside the Western mainstream. In the Soviet Union, the inexpensive twin-lens L introduced in 1949 made square format photography accessible to ordinary citizens. The Lubitel's square images—often capturing family gatherings, vacations, and everyday Soviet life—represent a different square tradition. One characterised not by artistic ability, but by accessibility within a collective communist system. It would appear this trajectory didn’t include the ‘elite’ or high-brow connotations that square might have enjoyed elsewhere.

China developed its parallel square format tradition with the Shanghai-manufactured Seagull and Double Phoenix cameras. These weren't mere technological imitations, but tools that created distinctive visual cultures. Some even see an intriguing historical connection, believing these designs consciously echoed the form of traditional Chinese seals. These official stamps—typically square with carved characters—had authorised documents and identity for centuries in Chinese bureaucracy and art. Whether intentional or retro-fitted, this idea shapes it as a cultural reframing, connecting modern photographic practice to ancient traditions.

"All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” _Richard Avedon

Social Commentary

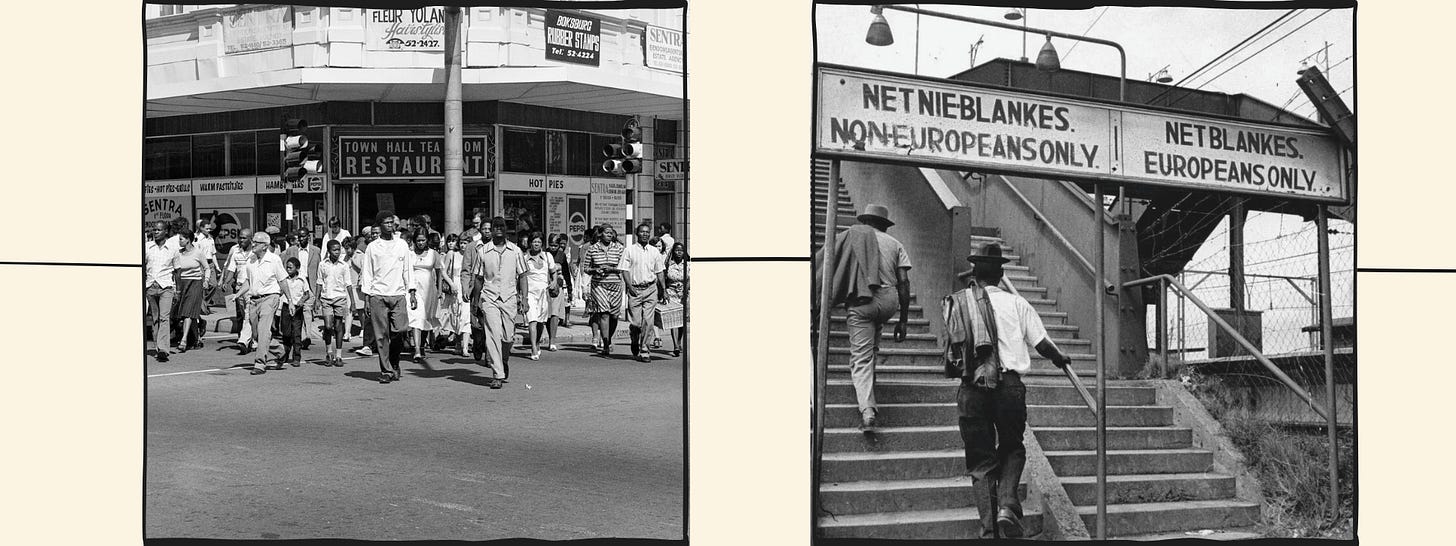

Across geographies, some photographers channeled the square's inherent equilibrium to examining societal imbalance. The discipline of the square format, a formal constraint, was sometimes seen to mirror strict social constraints being documented.

In apartheid South Africa, David Goldblatt and his Hasselblad's documented a rigidly structured society; Ernest Cole‘s landmark book House of Bondage (1967), included many square images seeming to provide a counterpoint to the profound inequalities.

What connects many of the documentarian photographers isn't just a choice of format, but their recognition of the square's unique potential for social commentary. A format that gave no preferential treatment to horizontal or vertical elements proved effective for examining societies where preferential treatment was built into the social fabric. The square frame became, paradoxically, a tool for highlighting imbalance—its perfect geometric regularity making social irregularities all the more visible.

This ties in to the ‘non-hierarchical framing’ I touched upon earlier; some critics argued the square format promoted a sense of objectivity by removing the inherent biases of horizontal or vertical orientations. Others countered that any framing is a subjective act.

Back in 1970s America, wedding photographers wielding Hasselblad medium format cameras charged premium rates due to the superior image quality and prestige associated with these cameras. The square format produced by Hasselblads became synonymous with luxury wedding photography, distinguishing it from standard rectangular shots captured on 35mm film.

"A square plate is a design element that has nothing to do with flavor, but it raises expectations for the food” _NYT

Beyond Photography

A Visual Grammar Tour

Besides framing our digital lives, the square has shaped how we saw and interpreted the world across vastly different cultures and contexts.

As a shape, the square is generally viewed as man-made; examples in nature are few and far between. The square's influence extends far beyond the lens, forming a kind of visual grammar across disciplines.

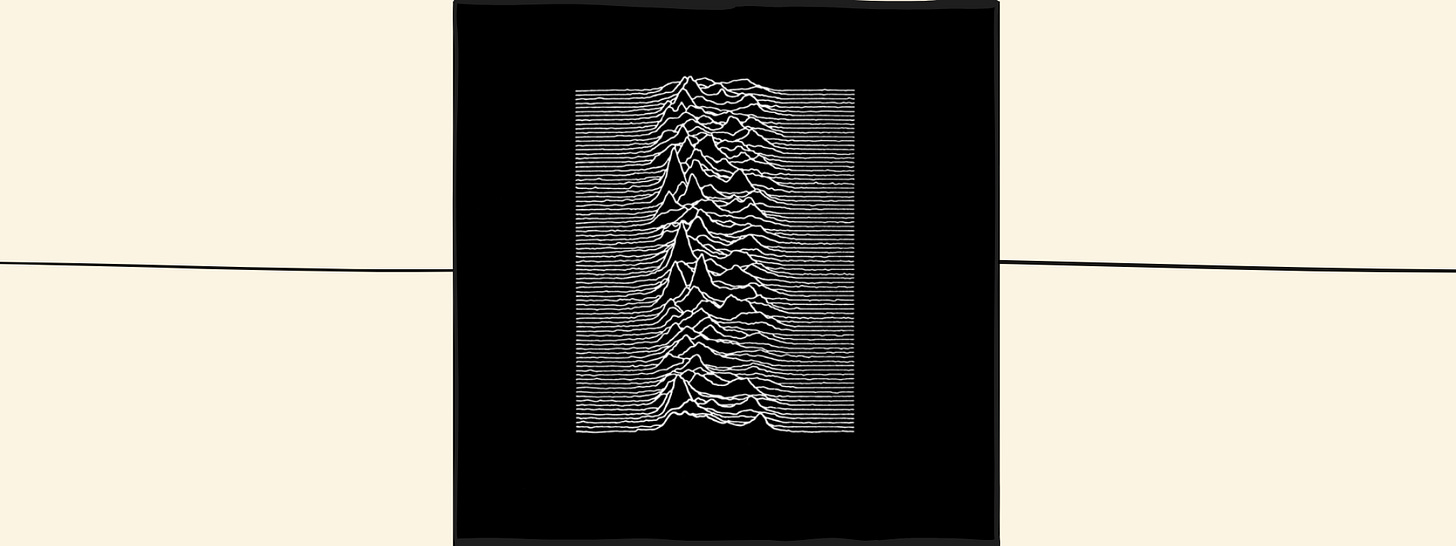

The vinyl record industry for years shaped a square visual language for music which continued into CDs and now the album ‘covers’ and thumbnails in Spotify. The 12-inch album cover became one of the 20th century's most significant square canvases. (British graphic designer Peter Saville’s iconic cover for Joy Division's "Unknown Pleasures" in 1979 became iconic; he placed the pulsar radio signals image in a perfect square, heightening the sense of cosmic order that made the cover so haunting.)

The square's geometric purity made it central to architectural movements. Both Bauhaus and Brutalism leverage the square shape to express their core principles of functionality, simplicity, and truthfulness in design, albeit with different aesthetic outcomes.

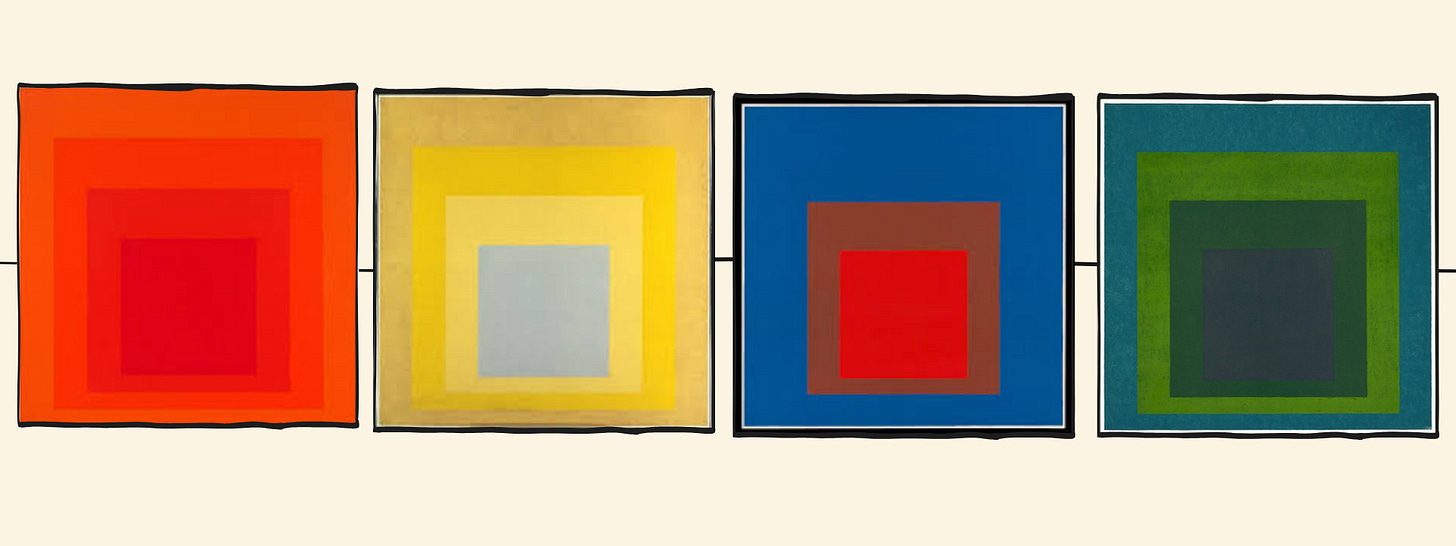

In a delightful tangent lies artist Josef Albers. Renowned for his ‘Homage to the Square’ series, he explored chromatic interactions within nested square compositions. Each of the over thousand 1000 paintings he made between 1950 and 1976, consists of three or four squares of solid colours, meticulously arranged to study the effects of adjacent hues. His series underscores the square's role in examining perception, impacting both abstract art and colour theory.

Another tangent is an offset from the landscape form, with one of the finest TV shows made, The Wire. Circa the mid-2000s, many TV stations still broadcast in a 4:3 ratio- this was a nearly square format, though admittedly not ever treated as square. As video moved more into widescreen, and The Wire (2002-2008) was filmed, creator David Simon insisted on sticking with 4:3, because he felt widescreen was "too pretty" for his gritty Baltimore story.

Culinary presentation has increasingly embraced the square, as restaurants became aware of how their dishes would be photographed for social media. Chefs and photographers now often consider the format- giving thought to how dishes might appear in square crops when designing plating and compositions. The bird's-eye "flat lay" of a meal, arranged within a square frame, has become ubiquitous that restaurants now design dishes with this perspective in mind.

The square has moved from being a way of capturing reality, to actually shaping it.

Being a square keeps you from going around in circles. _J. Vernon McGee

Hip to Be Square

And then, there’s linguistics. The term "square" has been used to describe someone conventional, old-fashioned, or out of touch with current trends. Originally, it emerged as a derogatory term in the 1940s jazz scene; used to describe people who didn't appreciate or understand jazz music. The term contrasted with being ‘hip’, or in the know

Then the phrase "It's hip to be square" gained popularity in the 80s and 90s. Why? Largely courtesy the 1986 song of the same name by Huey Lewis and the News. The song was inspired by the phenomenon of 1960s counterculture figures becoming more mainstream - cutting their hair, working out, but maintaining some of their bohemian tastes, Huey Lewis explained. He dubbed these people "bourgeois bohemians."

‘Hip to be square’ seems to playfully subvert the traditional meaning of "square" by suggesting that conventionality had become fashionable, though Huey Lewis joked that its was entirely not his intention for it to become an “anthem for square people.”

Full Circle

Once nudged into obscurity, then ushered back in by technology and nostalgia, now again toppled from its perch… has the square been ‘beaten out of shape’, as I wondered last week?

The digital/social default is now vertical. Many find it aesthetically unpleasing, but cannot deny its practical inevitability. Unceremoniously elbowed aside, the square finds itself once more in the realm of enthusiasts and nostalgists. Today, it is again a a deliberate aesthetic choice.

The push has not been without resistance. Profile pictures remained stubbornly square for a long while, before circles rolled in. Thumbnails in feeds often defaulted to squares. As recently as earlier this year, fans and Instagram users bemoaned when the iconic square grid homepage lost the battle. That homepage can now feature different ratios, losing its elegant array of equitably formatted images. Most Instagram photos (for a platform that is decidedly left its photographic roots) are still 1:1.

Perhaps a battle is not the way to look at it; a better take might just be that the square is finding a new equilibrium. Not mandatory, but not abandoned. Not the default, nor forgotten. Not ubiquitous, but not a relic. It has become something more valuable: a conscious, considered choice. This means something, in a time when machines, devices, algorithms choose so much for us, in the name of ease.

Someone today using the square format, knowingly or unwittingly, is choosing something with history; its cultural associations, compositional implications, visual grammar all coming to the fore. The format carries the weight of Hasselblad's stature, Polaroid's immediacy, Instagram's sociability, and countless cultural interpretations across time.

A simple geometric form—four equal sides, four right angles— contains multitudes.

As our visual culture continues to evolve, with new technologies enabling ever more format fluidity, perhaps the continued appeal of the square lies precisely in that- its constancy that wraps eclectic tastes.

The square reminds us that constraints are not merely limitations. The square forces us to focus on what remains. As in so much with creative endeavour, reduction becomes a path to clarity.

History suggests the square is unlikely to disappear. It has survived too many technological revolutions already, adapting and finding new relevance each time. In an increasingly fragmented visual landscape, where formats and durations and machine-generated and algorithmic feeds all collide, it could be that this elegantly neutral shape holds its own. Not demanding attention through its proportions, but its content.

As a construct, the square is both utterly artificial—a human construct versus nature's more organic forms—and yet instinctively natural in its mathematical symmetry. This paradox may be what makes it enduring.

“Now, think of a square, a living, beautiful square. And imagine that it must tell you about itself, about its life. You understand, a square would scarcely speak of its right angles, or of how its four sides are equal." - Yevgeny Zamyatin, Russian author

2. Friday Find: Burn It All

Make My Money’s latest spot features some easy-burning plants. And oh, also the comedian/actor Ambika Mod.

A UK organisation that “believes money should be moved from the destructive, harmful investments of the past”, Make My Money pushes citizens to ensure their money is pulled away from climate-destroying pathways. This is their fourth high-profile spot in the last year or so. It’s probably the one that least relies on an actor who owns the screen and grabs our attention, but all the spots have a clever undercurrent of playing with words, ideas and symbolic visuals.

This, and the first one with Kit Harrington & Rose Leslie (aka Jon Snow and Egret, real life couple), rely on a ‘reveal’, which is quite effective.

The two spots with incredible thespians Olivia Coleman and Benedict Cumberbatch (or more accurately, Oblivia Coalmine and Benedict Lumberjack) instead, waste no time in making clear the agenda, hitting us square on the head with the message, though delivered with oh-so-much class.

Oblivia Coalmine:

Benedict Lumberjack:

Since 2020, Make My Money has been “fighting for a world where we all know where our money goes, and where we can demand it’s invested to build a better future”; but the campaign is now shutting down as donations dry up, as CEO Tony Burdon shared a few days ago.

3. Don’t Believe.

The single most useful trait I have found in all my interactions with AI tools? Scepticism.

A healthy dose of, “wait, are you sure?”; generous sprinkles of “let me think about this a minute”; maybe some drizzles of “no way, Joon-hae”.

These are not merely useful, I believe they are critical.

Let me be clear. This is not AI-scepticism. We’ll leave that for another day. I speak here to every curious dabbler, casual user and every optimist who wants to cuddle up to shiny new AI tools (sometimes, that is me). All of us need the ability to pause while using them. I am speaking specifically of assistants, research tools and their output. Think Claude, Perplexity, ChatGPT.

Like many of us, I have grown to use them steadily more in the last year or so, beginning with hesitant sparring, reaching longer grappling. Slowly increasing my time spent, and how I deploy them. Much of it has been experimental or curiosity-based. “What if”, or “How will it handle this?”, or “What shape will it give?”.

I have increasingly also looked for ways to assist my research, finding perspectives that might otherwise be obscured from me. In this, I have evaluated how (and how much) they replace Google searches; and if they add value or speed or both, to the process of gathering information. The results are, more often than not, useful. Sometimes very useful indeed.

Equally, I have not yet been able to fully trust what is served up with such ease. When I have instinctively double-checked something, it has too often been the case that my instincts were justified. Facts that need to be verified; glib quotes that were just never said, likely opinions that were made-up. So much has sounded probable, believable, even sounded right… but just has not been. Separate research is needed to verify.

Or sometimes, a quick counter-question is enough.

“I apologise, I should not have said that”, I am told by my friendly AI fella (whether with a slight bowing of the head, or a nonchalant shrug of the shoulders, I can’t be sure).

The questions I think need answering are on the lines of,

“What makes you say that?”

“Why have you suggested this?”

“Are you sure?", or simply,

"Please verify that."

Again, I am generally positive on AI, and don’t attempt to resist its onslaught. I only try to see how the embrace can be thoughtful, considered, responsible even. So much of what these tools do is useful, impressive, and— let’s face it— sometimes stunning. But even in the face of the most special output, I would encourage us to always think,

“That’s cool, but-”.

Masala Peanuts

(where I share stories or tidbits I find interesting).

Read: A certain head of state has never heard of the country of Lesotho; so it’s probably a great time to know more about it. “Largest of the world’s three nation states to be totally surrounded by one other country, its mountainous terrain makes it the only nation in the world to lie entirely above 1000m.” Read this well-timed Cosmographia piece on Lesotho (

).Read: 404 Media uncovers the rash of AI video generators that Unleash a Flood of New Nonconsensual Porn. A number of AI video generators, mostly released by Chinese companies, lack the most basic guardrails that prevent people from generating nonconsensual nudity and pornography.

Read: K-pop giant SM Entertainment’s subsidiary training academy SM Universe will launch South-east Asia’s first K-pop training academy in Singapore. STudents are expected to be 13-18yrs old and the intensive 21-week training around singing, dancing and music production, and overall stage presence, will cost a cool US$10,000.

A fight between grasshoppers is a joy to the crow.— Lesotho Proverb